Service Life

Numerous records exist to map the 25 – 30 years of their existence captured by railway commentators and enthusiasts own observations and these have appeared from time to time in railway books, journals and magazines. Surprisingly new information still comes to light, especially from sources associated with railwaymen who ‘made it happen’ in whatever role they worked in.

This platform gives a focus by introducing/reproducing material, and although much of it is unlikely to be new it may provide additional knowledge. It could be influenced by engineering development, historic research or anecdotal accounts arising from the many sources available today in a multi-media environment.

Typical content at any point in time could include the following topics and will be refreshed from time to time in order to vary the content and theme.

| 1. Operating diagrams - Passenger and Freight | See below | |

| 2. Special events | N/A | |

| 3. Excursions | N/A | |

| 4. Unusual workings and locations | N/A | |

| 5. Performance - Load haulage, speed and efficiency | See Below | |

| 6. Trials | N/A | |

| 7. Accidents and incidents | See Below | |

| 8. Failures | N/A | |

| 9. Works & Servicing | N/A | |

| 10. Withdrawal and disposal | N/A |

1. Operating diagrams - Passenger and Freight

A new 4-6-0 intended for service in areas where Pacifics were too big or too heavy but what of other constraints....

From their introduction, the B17 design aimed to provide a more powerful engine capable of handling increased loads due to heavier trains on the GE section was realised but only a modest impact made in faster journey times on the main lines of East Anglia. Physical demands presented by gradients, complex junctions and marshalling yards fraught with speed restrictions and signal checks superimposed with tightly timed paths for intensive suburban services certainly occupied the two main routes radiating for up to 20 miles outside of Liverpool Street, giving constant scheduling difficulties. To preserve passenger revenues particularly on the Continental Boat Trains between Harwich and the capital in common with other towns and seaside resorts on the East Coast. Competition was already recognised from the inroads made by road transport in those same areas where journeys were not excessively long.

Transition

B17 footplate crews quickly set to work, adapting to left hand drive, to successfully develop new driving and firing techniques associated with the higher pressure boiler recognised as ‘a good steamer’ which provided improvements in efficiency with optimum valve settings to competently handle heavy loads on full regulator without fear of slipping.

The Boat Trains

On the ‘Continentals,’ little difference was evident compared with GE engines on the gradients with the exception of improved fuel economy in favour of the B17s, due to shorter cut off for the same journey time and load. During 1932, trials were conducted on the GE section to assess possible accelerations to certain other services from the terminus to Norwich, Southend and Cambridge. Despite good running confirming that the B17 was fully capable for the job and with capacity to handle extra load, nothing exceptional emerged to influence significant timetable changes. Locomotive availability appeared good including good mileage figures of up to 6,500 miles per month but this became less favourable without regular maintenance and the cumulative mileage increased. Boat Trains from Harwich also served the north of the country via the GN/GE Joint Line from March to Lincoln and beyond to Manchester and Liverpool, which became a regular diagram for B17s. To support this service to Manchester (and return) via Woodhead, Sheffield and Retford, a first allocation of B17s was made to Gorton on the GC section. This cross country service represented the longest diagram handled by a B17 of 220 miles, typically loaded to 14 coaches northbound although some were detached (or attached in the reverse direction,) at scheduled stations en route for the Midlands, the North East and Sheffield, to leave up to 10 coaches for the journey over Woodhead. A GC engine usually fulfilled the Manchester to Liverpool journey in both directions. For the B17 crew, speed was not usually of primary concern who given the demands ahead would normally maintain an even fire, reserving fuel for the climb over the Pennines. Nonetheless timing for this diagram in both directions only provided allowance to adjust the length of train at certain stations en route. All Boat Train services were suspended for the duration of the wartime period but were progressively reinstated prior to Nationalisation. However B17s were not allocated as the preferred engines for these services, which were progressively taken over by new class B1 4-6-0’s, then being delivered in increasing numbers to the GE section. Further changes occurred with the introduction of BR ‘Britannias’ from 1951 on to the Boat Train services and other expresses once the mainstay for B17s. By now, competition from road transport was adversely affecting services whilst at the same time the arrival of diesels and extended electrified services again impacted on the work of B17s leading to their eventual withdrawal by August 1960.

Further Afield

Various diagrams saw B17s also work on to the GC section from the early 1930s either from Doncaster with fish trains out of Hull and Grimsby to Banbury via Woodford and return or on the Manchester Expresses to London Marylebone and return with increasing regularity in the latter case by 1935. Shorter distances would also include trips to Nottingham Victoria and Leicester Central by Gorton engines. From 1936 B17s attached to larger LNER tenders providing much greater coal and water capacity were delivered new to Leicester and Neasden whose men had earned an impressive reputation for the best running over this part of the GC mainline, also known as the London Extension. Here the route, had been engineered and constructed on a vastly different basis without level crossings, sharp curves and the impediment of complex junctions and to the benefit of a continental loading gauge, compared with the GE in East Anglia. Resulting from this influx of B17s and to the credit of men on the GC section they quickly became accustomed to operating diagrams by day or night for express passenger, intermediate stoppers, express parcels and newspaper trains over significant distances and tight timings. Performance and reliability with increased loadings compared with earlier GC engines was the undoubted trademark of this developing combination between ‘man and machine.’ These B17s also created special interest from the stop watch fraternity who keenly measured and recorded their performance, but also from the public at large be they business people or working class – the attraction being the polished brass football surmounted by the brass nameplate of a well known football club with appropriate club colours to boot!

East Anglian – the business express

From 27th September 1937, a similar style of train travel to the successful high speed services hauled by A4s on the East Coast mainline was introduced between London and Norwich with an intermediate stop each way at Ipswich, to run on weekdays only. Two B17s Nos. 2859 and 2870 delivered new in June 1936 and May 1937 respectively were selected to operate this service, both entering Doncaster Works in July 1937 for conversion to a shortened streamlined version similar to the A4. Both emerged 1 week ahead of service start, sporting the wedge shaped front end, modified streamline casing which fitted over the existing boiler clothing plates (leaving the original lagging undisturbed,) rearranged cab side sheets and other details to generally resemble the A4 outline. A chime whistle was fitted in front of the chimney in typical A4 style. Tender side sheets were extended in height and formed to give a streamlined appearance. LNER green livery was retained but both engines were renamed; EAST ANGLIAN (2859) and CITY OF LONDON (2870) using straight nameplates, mounted on each side of the smoke box. Allocated to Norwich Thorpe, this was the first time locomotives with the larger tender would work on the GE section, following suitable upgrades. Operating diagrams were arranged to enable each engine to run in just one direction daily (dept. Norwich 11.55 am) on this prestigious train. The other engine was rostered on a following train with sufficient turnaround time to work the East Anglian in the return direction (dept London 6.40 pm.). In the event that only one engine was available, then the diagram would be altered to permit one engine to operate both trains on that day. The service did not operate at weekends and this time was reserved for maintenance and repair. However, the two engines were rarely absent from their primary duty.

This train was withdrawn at the outbreak of war and both engines were placed in temporary storage for 6 months. From February 1940 both returned to traffic on ordinary services. In common with the A4s, the side skirting was removed in 1941 to ease wartime maintenance whilst at the same time plain black became the standard livery for the period. Post war both B17s had a hum-drum existence, sometimes on purely local trains of modest proportions and operating as far west as Peterborough and regularly north to Sheringham. Short term reallocations to Yarmouth South Town, Ipswich and Cambridge saw them appear at Bury St. Edmunds and King’s Cross. Although the East Anglian service had been reinstated towards the end of 1946, the increasing fleet of new B1s provided greater flexibility and won preference by the crews compared with both streamliners. Now after nationalisation it became only a matter of time before both B17s were converted back (almost) to their original outline which was completed at Gorton in April 1951.

5. Performance

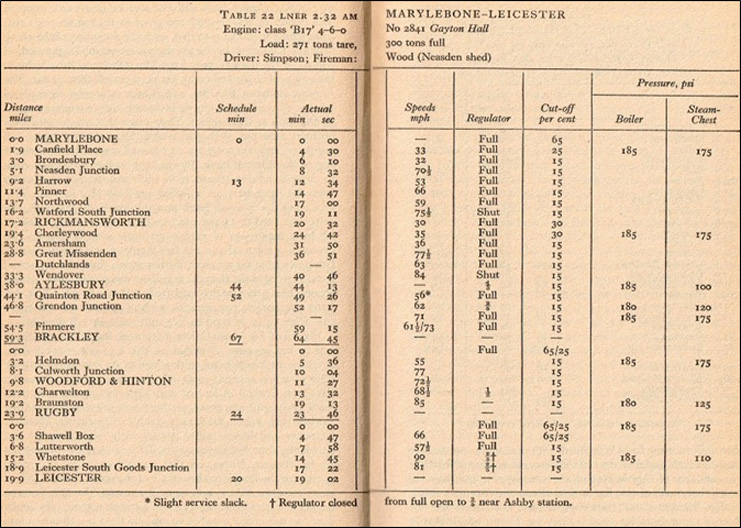

‘Down’ Newspaper Express - Marylebone to Leicester (circa 1936)

- 2841 GAYTON HALL (when allocated to GC section at Gorton) Footplate crew: Driver Simpson and Fireman Wood of Neasden

O.S. Nock records this as being his most exciting trip he made on a B17 departing London in the ‘small’ hours to deliver the News! Extracts are taken from his book LNER Steam (1969) and summarised in the log below.

Setting of at 2.32 am and in the best Gresley tradition, the engine smartly lifted its train on full regulator in the initial ascent from Marylebone to Brondesbury, then passing Neasden (5.1mlies) at over 70mph and uphill again to Harrow from where the climb continued through the Chilterns. Some 40 minutes into the journey speed touched 84mph at Wendover on the descent into the Vale of Aylesbury. Then Brackley (59.3 miles) was reached in 64¾ minutes from starting at the London terminus – some 2¼ minutes early. Notes indicate this was achieved at full regulator with 15% cut off and with steam chest pressure consistently maintained within 10psi of boiler pressure throughout by an experienced and determined footplate crew. From Brackley, even time was easily maintained to Rugby (a further 23.9 miles) with minimum speed of 68½ mph after the ascent to Charwelton marking a level section of the route, important because it was the location of water troughs installed in 1903 to permit non - stop running from Marylebone to Sheffield.

Then came an extraordinary start out of Rugby. The engine was given full regulator again and cut-off maintained at 25% to the top of Shawell Bank (some 5½ miles away.) Starting on the initial falling gradient of 1 in 176 speed quickly rose to a maximum of 66 mph (after 1¾ miles.) Shawell Bank was topped at a minimum of 57½ mph when the driver reverted to 15% cut off. Then beyond Lutterworth which is situated in a dip, the 1in 176 ascent to the summit of Ashby Bank was achieved and then to the magnificent finale! Ahead lay the 7 mile descent to Leicester. Full regulator was maintained for the first 2 miles from the summit during which time speed accelerated from 63 to 75 mph; the driver partly closed the regulator so that steam chest pressure dropped from 175 to 110psi as Ashby station was passed. With this latter pressure in combination with 15% cut-off speed rose again for the final 5 miles of the descent, this time from 75 to 90 mph, with the maxima attained on passing Whetstone. The engine developed this effort with the utmost ease and finished in characteristic style with top speed maintained to the very last minute. The run from Rugby to Leicester was achieved in a full 1 minute under the 20 minute scheduled for the 19.9 miles.

This run ably demonstrated the functioning of the Gresley front-end in the hands of a competent crew. Sir Nigel Gresley designed his engines to perform their work efficiently on a short cut-off and it was unusual to witness first hand one of these 3 cylinder types simply flying along up hill and down dale. Clearly the top link crews on the GC section had readily taken to the ‘Sandringhams’ which required totally different methods of handling from those long practised on the Robinson Atlantics, but from the outset they quickly developed the treatment required.

|

Log: Down Newspaper Express |

|

|

|

Log 1 |

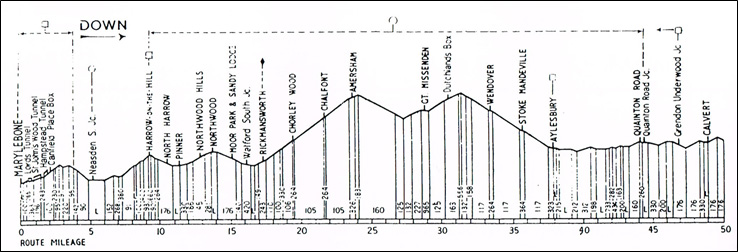

GRADIENT PROFILE: Marylebone to Calvert 48.8 miles

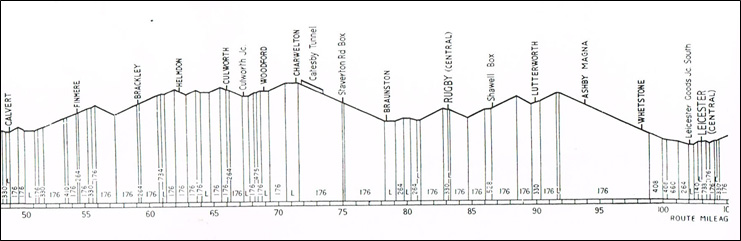

GRADIENT PROFILE: Calvert to Leicester 54.3 miles

The subsequent examples are referenced timing logs for comparison purposes over both similar and different routes and distances and different train weights. These currently appear without the text detail or the gradient profiles (tba).

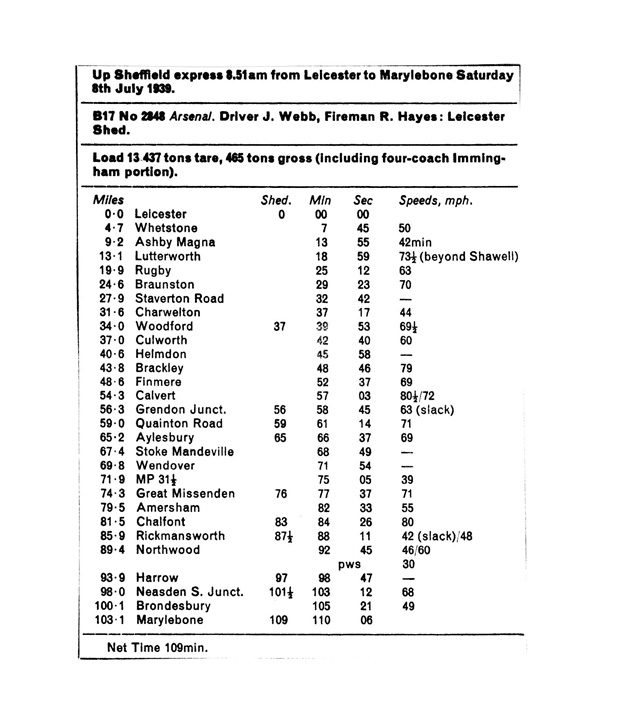

Example 2 taken from O.S. Nock LNER steam 1969

Example 2 shows the timings of the 08.51 Leicester to London Marylebone with a load of thirteen coaches hauled by 2848 Arsenal (See Log 2 below)

|

|

Log 2

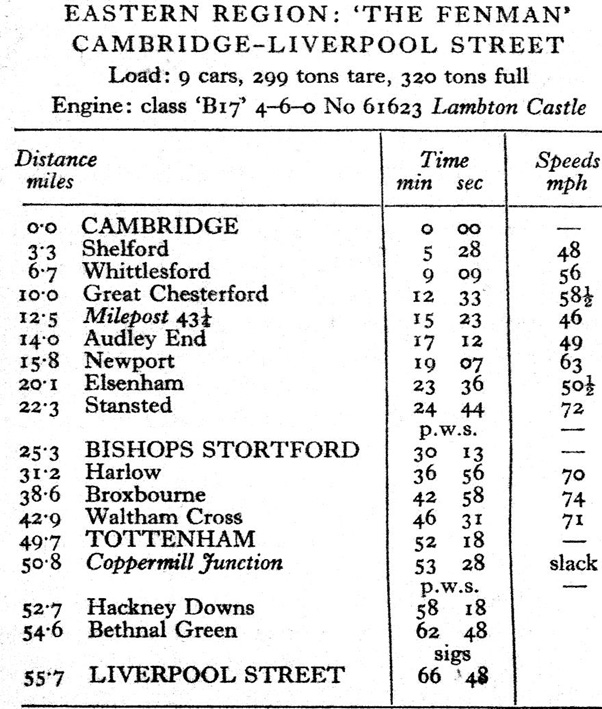

Example 3 taken from O.S. Nock LNER steam 1969

Example 3 shows the timings for “The Fenman” from Cambridge to Liverpool Street with a load of nine coaches behind 61623 Lambton Castle. (See Log 3 below)

|

Log 3

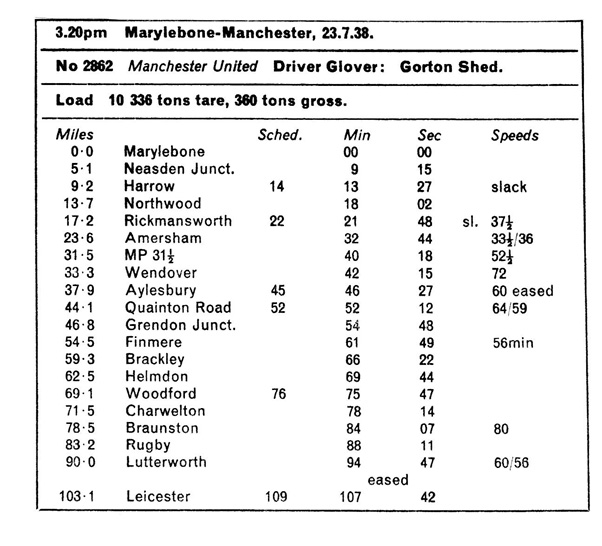

Example 4 taken from The LNER 4-6-0 classes by John F. Clay and J. Cliffe

This example details the 15.20 Marylebone to Manchester up to Leicester. The locomotive was 2862 Manchester United and hauling 10 coaches. (See log 4 below)

|

|

Log 4

Example 5 taken from The LNER 4-6-0 classes by John F. Clay and J. Cliffe

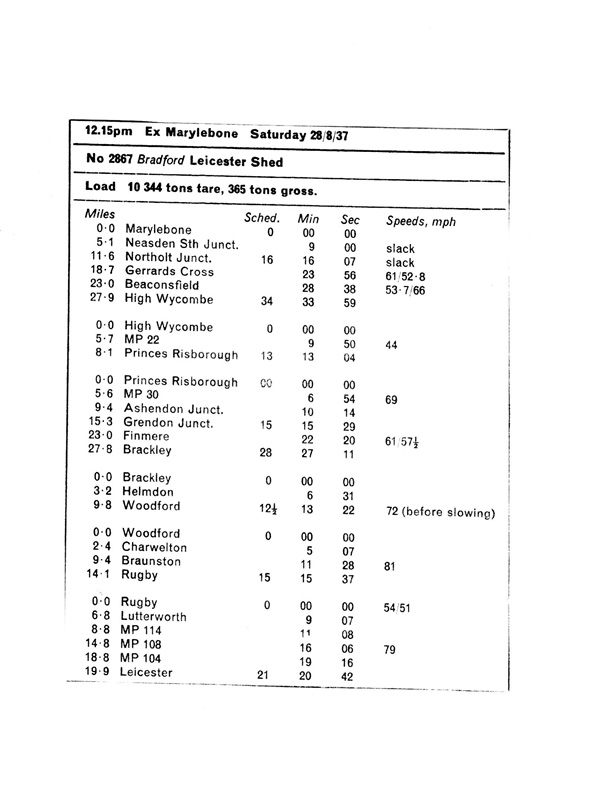

This log records the run for the 12.15 London Marylebone to Leicester on Saturday August 28th 1937, a train of ten coaches hauled by 2867 Bradford. (See Log 5 below)

|

Log 5

Example 6 1931 Tests 4-6-0 Sandringham class locomotive,

Cambridge was reached in 61 minutes from Liverpool Street, including a stop at Bishop's Stortford; the distance is 55¾ miles in late 1931. Locomotive Mag., 1932, 38, 34

Example 7 Harvey, D.W. Bill Harvey's 60 years of steam. 1986. Page 135:

"October 1947 was memorable for a series of trials carried out on the Colchester main line with the NER dynamometer car and its team of four test engineers under the supervision of D. R. Carling, for the purpose of establishing which of two locomotives, identical in every respect apart from the number of cylinders, was best suited for the service. The two were class B17 No 1622, Alnwick Castle, with three 17½in diameter cylinders and No 1607, Blickling, rebuilt as Class B2 by Edward Thompson with two 20in diameter cylinders.

Both types had a common stroke of 26in and boilers pressed to 225 lb/sq in. I was privileged to ride in the dynamometer car when No 1622 was being tested with a trailing load of 313 tons including the dynamometer car on the 10.10am semi-fast train to London, returning with. the 3.40pm express. A peak figure of 1,050 drawbar horse-power was exerted in lifting the train out of the Stour valley, up the two-and-a-half miles of Dedham bank, which has a gradient of 1 in 134.

RCTS Locomotives of the LNER Part 2 page 101 covers these tests in greater detail and makes it clear that the B2 was less efficient than the B17. This could have initiated the decision not to complete the B2 conversion programme and to fit the 100A boiler to the remaining B17s.

Further references

The EAST Anglian express. Rly Gaz., 1937, 67, 646-8. 3 illus., diagr. (s. el.), plan.

L & N.E.R.. Loco. Rly Carr. Wagon Rev., 1937, 43

The "EAST Anglian" trains, 339-41. 3 illus., diagr. (s. el.), plan.

Mainly about rolling stock and train times which attained Notional Express levels. No. 2859 East Anglian illustrated

Engineer, 1937, 164

STREAMLINED L.N.E.R. engines., 426-7. illus. Robson, T . The counter pressure brake method of testing locomotives. J. Instn Loco. Engrs, 1943, 33, 171-98. Disc.: 198-217 (Paper No. 441).

Describes testing a B17 locomotive by this method.

Loco. Rly Carr. Wagon Rev., 1941, 47, 151

[STREAMLINED B17 No. 2780 City of London: a record of continuous performance between Liverpool St. and Norwich, in which 100,103 miles were run in 452 days.].

Rly Wld, 1978, 39, 483-7.

Jackson, David and Owen Russell. 'North Country Continental' 1927-39. Through working with lodging turns was instigated between Ipswich and Manchester using B12 class and then B17 class locomotives. Includes photographs on No. 2806 Audley End at Deepcar, B12 No. 8577 at Worksop, No. 2806 at Worksop, Driver Pinkney in cab of No. 8535 and No. 2807 Blickling at Sheffield.

Rly Wld, 1981, 42, 13-17.

Jackson, David and Owen Russell. The 'Footballer' interlude: G.C. Section notebook. B17 with football club names and standard tenders on use on Great Central route between 1936 and 1939.

Neve, Eric. The last LNER luxury expresses – the 'West Riding Limited' and the 'East Anglian'.

Includes logs of runs: the East Anglian was aimed at giving the Norwich and Ipswich businessman a full afternoon in London and enough time in the office before a fast transit to London: the LNER obviously hoped to lunch and dine its customers en route. Speeds were not high and unlike Bristol, Norwich now enjoys far better times, and still retains its restaurant cars.

7. Accidents and Incidents

Investigations into most accidents show they could have been prevented, but nonetheless they still happen and may claim victims as a consequence..............

7a B17s – always first!

The very first incident involving a B17 when working its first train to Norwich was first of class No. 2800 SANDRINGHAM which fouled the edge of the station platform as it passed through Needham Market. A description of the severity of the damage to either engine or platform is not known but apparently the coping stones along the edge were immediately moved back to avoid any reoccurrence. Continuing this theme, the first derailment of a B17 involved 2804 ELVEDEN in late January 1929 when allocated to Parkeston, working the ‘Up’ Flushing Continental at Wrabness, just 5½ minutes into the journey after departing Parkeston Quay heading to Liverpool Street. This was about 1 month after delivery of the engine ‘as new’ from the North British Locomotive Company’s Hyde Park Works. Single line working had been introduced using the ‘down’ road following the derailment of goods wagons nearby. However, a set of trap points in the path of ‘the Continental’ were not secured ‘closed.’ Consequently the engine ran through these and came to rest on the ballast. Fortunately there were no serious injuries to the footplate crew, passengers or other railway staff.

7b Someone else’s error

No. 2808 GUNTON was also the victim of someone else’s error. This occurred in the fog on 4th October 1929 soon after 5.15 a.m. at Tottenham North Junction working the early morning ‘down’ Norwich express consisting of 12 coaches. A freight train consisting of 20 empty coal wagons had been brought to a halt at the North Junction home signal on the branch from the West Junction. After standing for about 10 minutes the engine driver of the freight train thought he heard the sound of the signal arm dropping and moved forward without any further check to ensure the path was clear. The signalman saw the advancing freight train force its way through the points and immediately ran to his cabin window to show a red light, shout a warning and change all signals to danger. Despite the driver of the express observing the pending disaster and making a full application of the brake, it was too late to prevent the collision. By now, some 20 yards past the junction, the driver and fireman of the freight train saw the express, abruptly stopped and jumped for their lives. 2808 was derailed as it struck the freight wagons but continued for another 140 yards ending up at a precarious angle amongst the wreckage of mangled wagons and torn up track and sleepers. Fortunately there were no fatalities or serious injuries. Arising from the subsequent enquiry, the responsibility for the accident was attributed entirely to the driver of the freight train. Following repair at Stratford GUNTON went on to be the longest survivor of the class achieving over 31years service.

7c High speed derailment

In comparison with the previous accounts, heavy damage to coaches occurred as a result of this derailment at Sleaford North Junction on 15th February 1937, with unfortunate loss of life amongst a nearby group of platelayers. No. 2829 NAWORTH CASTLE (a March engine,) was running late on the ex 10.25 am York to Lowestoft express and entered the junction subject to a maximum 20 mph speed restriction. Travelling at about double the permitted speed (as later assessed by the accident inspector) both engine and tender completely left the track but remained upright. However the coupling between the first coach and locomotive tender broke and as a result the first 3 coaches slewed on their sides to crush the occupied platelayer’s hut – it was lunchtime. The train was well loaded but fortunately only minor injuries were sustained by passengers. Miraculously the head ganger survived this awful disaster – he lived locally and by chance had returned home for lunch. Next day 2829 was taken to Doncaster for repair, to emerge 2½ months later with speed recorder fitted. Coincidently, later that same day a second derailment occurred at Sleaford involving a diverted freight train reportedly speeding across the junction. Details remain scant with just two lines of comment reported in a local newspaper at the time. Presumably no serious injuries or fatalities occurred because reports of this second accident have not been found. Certainly no official record could be identified during a search of the Ministry of Transport reports into railway accidents at the NRM. Temporarily north – south diversions were routed via Boston until normal service could be reinstated.

7d SPAD 1

On 10 February 1941, locomotive No. 2828 Harewood House was hauling an express passenger train that came to a halt between Harold Wood and Brentwood Essex as it was too heavy for the locomotive. A passenger train overran signals and was in a rear-end collision with the express. Seven people were killed and seventeen were seriously injured.

7e. SPAD 2

On 2 January 1947, locomotive No. 1602 Walsingham was hauling an express passenger train that overran signals and was in a rear-end collision with a local passenger train at Gidea Park Essex. Seven people were killed and 45 were hospitalised.